The Shaping Shack

Johnny Rice is a lifetime surfer who rides the waves during the week and makes his living by shaping surfboards in his backyard on weekends. He has a favorite saying: "Surfing is good for you in four ways: physically, mentally, emotionally and spiritually." The 63-year-old Santa Cruz native lives and breathes what he prescribes.

The life of a surfer means living according to the rhythms of the tide's pull and not the daily 9-to-5 grind. By running his own business, Johnny—a former coast guard officer and merchant marine captain—makes his own schedule according to when the waves are up and is able to take time off to travel to other surf destinations. Shaping boards for other people is also a way to make others happy, which is what Johnny finds fulfilling.

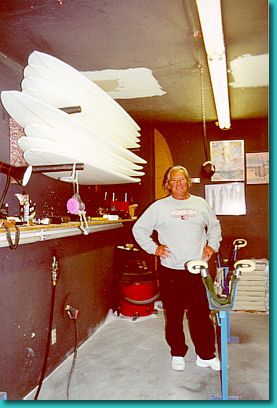

The boards are made in the "Shaping Shack," in Johnny's backyard, where he has hundreds of mix-and-match templates that he created. The shack is where the blanks of hundreds of surfboards are transformed from foam and stringer, a strip of wood that runs down the middle, to customized pieces of art—a personal extension of the surfer.

Part of Johnny's approach to shaping a board is to understand the surfer. "I like to watch them surf and see how I can improve them," he said. Part of this is intuition and part of it experience. He meets with clients one-on-one, seats them at a picnic table next to a running rock fountain in his yard, and takes notes.

Johnny's been around the world—he lived three years in Hawaii and eight years in Brazil—and has been shaping for more than 45 years. He's still a pretty easygoing, down-to-earth fellow.

Custom boards are better, in Johnny's opinion. But of course, he's biased. "If you go to a store and buy a board off the rack, it does you no good because you don't know what the hell you're going to get," he said. "The best thing is you go to a shaper and you tell him where you surf, how you like to surf, how much experience you got, how much you weigh."

Johnny doesn't like to elaborate too much on the techniques of shaping but knows what he needs to ask his customers to make a good board. He notes the surfers' weight, experience level and the kinds of waves they surf. Once he gets all that down, he cuts out the blank to fit the desired template, planes it down to the desired thickness, and shapes the rails. He sands it down until smooth, adds the extra features and sends the board to a professional glasser.

Johnny uses only UV solar resin, a recent product that is better for the environment. He believes that every surfboard maker should use it out of concern for the ocean's health. "The water is the Mother Earth's blood, and if it gets polluted, then she's going to get sick," he said. "Then what's she going to do?"

Johnny can be solemn and reflective at times, but most of the time he's full of jokes and makes people laugh. He enjoys when visitors come by to "talk story" about the waves.

For the surfboards, he offers extra features: a fin, tail block, nose block or a three-fin box. Fabric can be special-ordered from Hawaii to decorate the face. He can't tell you exactly what makes a good board, other than it reflects the uniqueness and style of the surfer.

A beginner probably wants a longer and lighter board compared with the shorter, slimmer one an advanced surfer would ride. The more advanced the surfer, the sharper the rails, or edges on the sides of the board. Long boards, short boards, unusual boards, whatever a customer wants is possible. "I can make anything," Johnny said.

But that doesn't mean he'll make a board for anyone who comes by. Johnny has turned away customers—more and more of whom arrive from Silicon Valley. The main reason? "Arrogance," he said. "Some of them are nice and considerate and truthful." But some like to exaggerate about their surfing abilities. "If I ask about your surfing experience and then you lie to me, how can I make you a good board?" he said. "If you talk 'big talk' to me, how can I make a good board? When you talk to me, you have to be honest."

Because of his own heritage, Johnny particularly enjoys making boards for women and people from diverse ethnic backgrounds. "More women ride my boards than any other board," he said. In September, Johnny was surprised to receive an award from Women on Waves for his support of women surfers and his sponsorship of a local women's surfing team. "That was quite an honor," he said. "Men never get anything from that Women on Waves thing."

Johnny has his own logo—a triangular wave—but he doesn't pay for any advertising to promote his business. Instead, he relies on word of mouth and his web site, which brings him clients from around the world. His boards caught the eye of an entrepreneur named Masahiro Baba, who now orders Johnny's boards regularly and sells them in Japan. Once Johnny finishes a board, he personally signs each one. "If I make you a board, it's going to be beautiful," he said. "I guarantee it. Everything is hand done. Nothing is machine made here."

The Life of a Surfboard Shaper

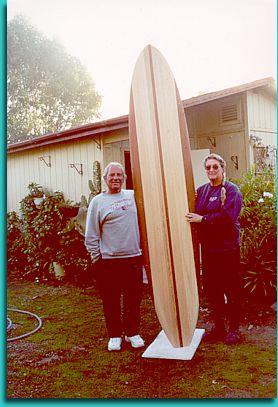

Johnny

and Rosemari are serious surfers. For both of them, surfing is a way of life.

They even got married surfing. At dawn one summer morning, the wedding party

paddled out on their boards. Johnny and Rosemari exchanged vows surrounded by family, who were

also on boards, and then cruised the waves back toward the beach. The priest—also

a surfer—strapped the marriage certificate to his wet suit in a plastic

pouch. Johnny and Rosemari have five kids and seven grandkids—all of

whom surf.

boards. Johnny and Rosemari exchanged vows surrounded by family, who were

also on boards, and then cruised the waves back toward the beach. The priest—also

a surfer—strapped the marriage certificate to his wet suit in a plastic

pouch. Johnny and Rosemari have five kids and seven grandkids—all of

whom surf.

The couple first met in high school. It was "love at first sight," Johnny insisted, "and she's still my girlfriend." As a matter of fact, he taught Rosemari how to surf and made her first surfboard. Rosemari still remembers: "It was a balsa board, all blue, with my name written on the nose of the board, painted in yellow." Rosemari began surfing at San Onofre in 1954 and was the first woman to compete on Dewey Weber's Surfing Team in 1962. Both Johnny and Rosemari still participate in local competitions on occasion but can most often be seen enjoying the waves on the Santa Cruz coastline.

Hanging around surf legend Dale Velzy's surfboard shop down in Venice Beach is how Johnny got his start in shaping at the age of 15. When his family moved to Southern California in 1954, Johnny used to spend his days watching Velzy and sweeping the shavings from the floor. Velzy would pay him to sand the boards after he finished shaping them, at 50 cents a side. "That gave me enough for gas and beer for Rosemari and me," he said. Then one day in February, Velzy asked Johnny, "Hey, you wanna learn to shape?" And that's how he became one of Velzy's apprentices.

Today, Johnny credits Velzy for teaching him everything he knows. The boards were all made of balsa then, and learning to make one required patience. "In the old days, you had to learn everything," he said. "Where the wood grain is, how to sharpen your tools, how to make a part, how to repair it, how to glass—you had to know the whole thing."

He still knows how to make a balsa board. Last year he began crafting a striped, redwood-and-balsa board that's still a work in progress. The creation is a copy of a board he had when he was 12. Just shaping such a board can take up to 60 hours. "I always need my wife helping me," he said.

Johnny comes from a line of Santee Dakota Sioux and Prairie Band Potawatomi. His parents grew up on a reservation far from the ocean, but Johnny's love for surfing came from his exposure to the surf culture in Southern California.

Johnny tells the story of his first surfing experience, in August 1949. He was at Cowell's Beach. "My first board was 14 feet long and weighed 125 pounds. I weighed 98 pounds, and I dragged it down to the beach, stuck an old wine bottle in the hollow [surfboards were hollow back then]] and that was it," he said. "I couldn't believe it. I thought, this is good. This is great. This is what I'm going to be doing for the rest of my life." Like most surfers in those days, he taught himself to surf by watching others and managed to stand up the first time he tried. He bought his first board, which he named "The Octopus," from big-wave rider Fred Van Dyke.

The surfing lifestyle brings with it a desire to surf the best waves, and that compels surfers to travel the world seeking them. Following his apprenticeship with Velzy, Johnny found himself in Hawaii for three years as a beach boy on the Big Island. After that he returned to Santa Cruz, but went on another journey nearly a decade later. This time he went to Brazil, where he stayed for eight years, running a surf shop in Praia do Tombo and raising his kids.

"It was just starting when I got down there," he said. "It was the small-board era, and (surfing) got bigger and bigger, and now it's huge. Some of those guys had these geezerlike little boards made out of Styrofoam. So I made them a couple of boards and now they're champions in Brazil. They won prizes and bought homes for their mothers and they're no longer poor." Many locals of the Sao Paolo area credit Johnny with bringing the first real surfboards to them. He enjoyed living in Brazil. "Good music, good food, good people," he said. "Good surf."

Passing on the Knowledge

Has he taken in any apprentices? Not yet, he said, but he thinks one of his grandsons may be interested when he grows older. He is well aware that the craft is slowly disappearing. "It's being lost now because there are very few of us who can do it right from the beginning." The ideal student is someone with talent and patience. "He's such a perfectionist," said Rosemari, "he'd want anyone learning to do it perfect, and that's hard."

The

cottage where Johnny and Rosemari live is a little surfboard museum in itself.

All kinds of boards hang from the ceiling and the walls and line the floors,

next to colorful rugs, oil paintings of favorite surf spots and photographs

of surfing friends.

The

cottage where Johnny and Rosemari live is a little surfboard museum in itself.

All kinds of boards hang from the ceiling and the walls and line the floors,

next to colorful rugs, oil paintings of favorite surf spots and photographs

of surfing friends.

The style of surfboards seems to travel full circle, in the same way fashion recycles itself. Long boards, for instance, went out of style for a while during the '70s and came back in the '80s. During the first long-board competition in Santa Cruz in the '80s, Johnny remembers everyone scrambling to find one.

The greatest change will most likely be in the materials used to make surfboards. "Lighter foam, harder glass. Maybe it won't even be called glass." He is not against progress, and from time to time he experiments with different types of surfboards. Everyone aspires to make a better board, he said. But he stills feel nostalgia for balsa.

Johnny believes it's important to preserve some traditions. Coming from a bicultural background, he feels the pull between the old and the new. Although he found a new identity as a surfer growing up in Santa Cruz, he never shucked his identity as an American Indian. He spent six years as a pipe carrier and sun dancer, but won't go into detail about the experience because he said it was "sacred."

"People ask, 'Don't you get tired of making surfboards?'" he said, leaning back and basking in the sun that slants into his backyard. "No, I'm not tired of making them. I enjoy getting in there and making those boards. I enjoy surfing. I enjoy my job. I enjoy my friends. Life is good."

Home | City Notes | Restaurant Guide | Galleries | Site Map | Search | Contact