"See Us If You

Are Contemplating Marriage, Suicide or Crime!"

The Saga of Holy City, California

By Andrea Perkins

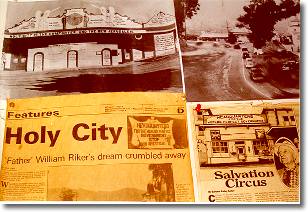

Current maps of Santa Cruz county still mark the spot as "Holy City," yet very little remains of this once booming West Coast mecca. Sixty years ago, it was a well-known stopping spot for travelers along the twisty Old Santa Cruz Highway. Today, all that testifies to its strange and colorful past is a rickety old post office, a quaint shed and a house.

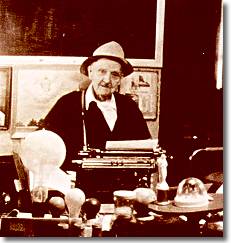

The house belonged to "Father" William E. Riker (right, circa 1950-55), a.k.a "The Comforter," and was one of the only structures to escape a series of mysterious fires that caused the town's demise.

photo

curtesy of Tom Stanton

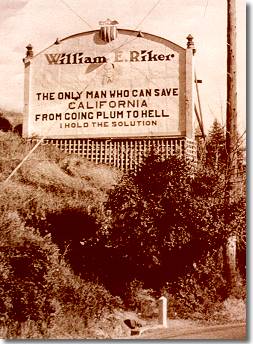

Holy City sits in an obscure corner of the lush wilderness 10 miles south of Los Gatos, on what was once the only route between San Jose and Santa Cruz. Established in 1919 by Riker and a small group of his loyal disciples, the city was initially built on 30.25 acres bought for $10 the year before. Soon it was bustling with tourist-oriented businesses. Flimsy wooden structures with carnivalesque murals and slogans lured weekend motorists. Garish billboards lined the highway, describing Holy City as the future center of the world, a true utopia, a paradise. "Holy City answers all questions and solves all problems!" "See us if you are contemplating marriage, suicide or crime!" One sign even declared the city to be the "headquarters for the world's most perfect government." Folks from nearby towns came by for ice cream on Sunday afternoons to watch the show. Interestingly, although it was publicized as a religious site, not one church was ever built in Holy City.

Sign

on Old Santa Cruz Highway, circa 1930

photo curtesy of Tom Stanton

photo curtesy of Tom Stanton

Riker was a handsome, blue-blooded California native, born in 1873 and described in contemporary accounts as "a favorite of the ladies.'' His first job, which involved reading palms, earned him the nickname "The Professor." Later, he toured the country as a mind-reading act, a lucrative career that ended abruptly when bigamy charges were filed against him in San Francisco. Leaving both his wives behind, Riker fled to Canada.

It was there that he developed "The Perfect Christian Divine Way," a credo that involved total celibacy, abstinence from alcohol, hard-core white supremacy and communal living. From what few records still remain, it seems that "being born again" was also somehow integral to the project. Armed with this new doctrine and a plan, Riker returned to San Francisco and started a commune. The city on the bay would later grow accustomed to such enterprises, but at that time, more than a few eyebrows must have been raised.

The first thing Riker did was make his followers give him their money, freeing them from worldly concerns to pursue their spirituality. By 1918, he was able to buy the land on which to establish his new Jerusalem and to house about 30 devotees, most of them elderly.

Riker apparently considered himself exempt from the celibacy rule, soon taking a bride by the name of Lillian. Incensed by this action, a certain Frieda Schwartz, one of Riker's earliest disciples, sued him in an attempt to recover the funds she had relinquished upon entering the Perfect Christian Divine Way. She lost, and the publicity the case received only succeeded in drawing more tourists to the area.

Soon Riker was raking in $100,000 a year on the proceeds from a restaurant, a service station and an observatory where visitors could look at the moon through a telescope for 10 cents. He was also running a mineral water business on the side. As early as 1929, Holy City had a weekly newspaper and a short-lived radio station, the second to be licensed in California, that went by the call signal KFQU. Due to "irregularities" (perhaps including its name), its licence was revoked in 1931, thus putting an end to a popular half-hour show with a Swiss yodeler.

In the 1930s, the population of Holy City's swelled to 300 and Riker embarked on a series of attempts to become governor of California. In 1943, after his fourth try, "The Comforter" was arrested due to his pro-German sentiments, as manifested in his rabid letters of support to Adolf Hitler. During the trial, his lawyer, the illustrious Melvin Belli, persistently referred to him as a "crackpot." Riker escaped persecution, but filed suit against Belli for defaming his character. Riker lost the case.

This marked the beginning of the end for Holy City. In 1940, Highway 17 opened, replacing the narrow, winding Old Santa Cruz Highway, which to this day gets very little traffic. Tourism in Holy City dropped significantly. In 1959, Riker lost most of his land in a complicated real estate transaction, followed by a series of mysterious fires that consumed most of what remained of the town and left only a few haphazard remains. The records at Historic Spots in California indicate that Riker lingered on the few acres Holy City had been reduced to until 1966, at which time he astonished the handful of his remaining followers by converting to Catholicism. He was 93.

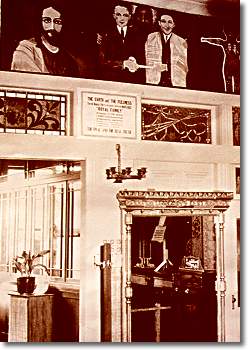

Old

post office interior circa 1930

photo curtesy of Tom Stanton

photo curtesy of Tom Stanton

photo by Andrea Perkins

(click for enlarged view)

(click for enlarged view)

"He certainly was a nut," says Stanton. "Come on. You've got to see something."

Behind the shop is an empty meadow, graced by a single blooming hawthorn tree. "Sometimes hippies come by,'' he says, "and ask if they can camp here. I let them."

At the edge of the meadow looms what Stanton calls "the largest and most complete ring of redwoods you will ever see." A wall has been built around them. "I don't know who built that wall," says Stanton. "But I've got a pretty good guess."

The bases of four trees form a sort of altar. "The nuns come here every month to pray," he adds mysteriously. "Nice ladies. I don't ask them where they're from. I just let them in."

photo

by Andrea Perkins