Home | City Notes | Restaurant Guide | Galleries | Site Map | Search | Contact

With all the thought on terrorism and war, I decided to see if it were possible to think about anything else. If I succeeded, it would be a first among publications; and if I failed, folks could just shake their heads and say, "darn fool thing to try." But what to think about almost stopped me dead. Was there really anything else? After long consideration and several bouts of depression over my inability to churn up other thoughts, I came up with what I thought to be a fitting topic: Now don't laugh; I came up with the idea of writing an article on fishing. That seemed pretty American and patriotic and not likely to cause anyone offense. After all, I didn't want to end up before a military court with Taliban John from Marin and embarrass my family. So here goes. Wish me luck. I will surely need it.

I have been a fisherman all my life, more or less. But in the last few years I have been a fisherman more in theory than in fact. Truth to tell, I have failed to fish. And having failed to fish, I have failed to stare hard into very many creeks, which one does when out fishing and the fish are not biting and the beer is running out. But to get to the point, I began to wonder how our creeks were doing, you know, health-wise. Were they nice little creeks, full of fish and pretty, or were the fish gone and the creeks trashed, as some environmentalists have been saying? Boy, those environmentalists sure do know how to be negative, don't they!

Well, since I was going to be doing some non-war thinking, why not think about the creeks on the North Coast of California. Problem is that one can not think about or look too seriously at those creeks these days without a fishing license, and mine had expired. So my first thought was to get a fishing license. That way I could get a firsthand look at some creeks and even probe a few for fish. So I got a license and also a copy of the fishing regulations to find out if there was anything I should not be doing. My did it turn out there were things I should not be doing. One of them seemed to be fishing!

Okay, I'm off to a good start here. Two paragraphs without a thought about war or terrorists or Afghanistan or ... Okay, better stop right now.

As I was saying, the regulations have changed considerably since the days when there was either no limit or the limit was so high I could never catch that many fish or drink that many beers. Now, it seemed, on my favorite streams north of San Francisco the limit was one "hatchery trout or hatchery steelhead" per day. But as my goal here was sustained thinking about something other than you-know-what, I began to think about this a lot. I began to wonder: Are there "hatchery" trout or steelhead in these creeks? And if there were, how would I know the difference?

The

regs came to my aid here on page 46 where it states at the very end of

Article 3 ("Alphabetical List of Waters With Special Fishing Regulations")

of Chapter 4: "Hatchery trout or steelhead are those showing dorsal

fin erosion and/or an adipose fin clip." This, I thought, might be

a problem, so I asked at my local fishing shop. Leland Fly Fishing Outfitters

is located in San Francisco on Bush Street next to Le Central Restaurant.

This is in the heart of the financial district and both establishments

have many lawyer clients. I guess on a bad day you have a couple martinis

at Le Central, then go next door and buy some fishing gear and forget

it all. That's what fishing is, or used to be, all about, right? So what

if your silly, non-fishing client is going to jail for the next ten years?

Anyway, the guy at Leland Outfitters indicated that Hatchery vs Non-hatchery

(aka "native") could be a tough call. Now since I am not a lawyer,

I realized that I needed to be careful here. Not only would I be paying

Leland Outfitters for my fishing gear, but I would be shelling out bucks

to some boozed up fish lawyer.

The

regs came to my aid here on page 46 where it states at the very end of

Article 3 ("Alphabetical List of Waters With Special Fishing Regulations")

of Chapter 4: "Hatchery trout or steelhead are those showing dorsal

fin erosion and/or an adipose fin clip." This, I thought, might be

a problem, so I asked at my local fishing shop. Leland Fly Fishing Outfitters

is located in San Francisco on Bush Street next to Le Central Restaurant.

This is in the heart of the financial district and both establishments

have many lawyer clients. I guess on a bad day you have a couple martinis

at Le Central, then go next door and buy some fishing gear and forget

it all. That's what fishing is, or used to be, all about, right? So what

if your silly, non-fishing client is going to jail for the next ten years?

Anyway, the guy at Leland Outfitters indicated that Hatchery vs Non-hatchery

(aka "native") could be a tough call. Now since I am not a lawyer,

I realized that I needed to be careful here. Not only would I be paying

Leland Outfitters for my fishing gear, but I would be shelling out bucks

to some boozed up fish lawyer.

With

this thought in mind, I began to turn up the mental heat. There in fact seemed

to be two big questions: First, were there hatchery fish to be found in the

creeks where I wanted to fish? Second, would I know the difference if I caught

one? These thoughts almost made my head hurt. But it was good, as I was no

longer thinking about the other thing. Al Queda, anthrax, bin you-know-who

(okay, I shouldn't even be saying those words) were now far from my mind.

I had bully questions, something reporters love, and I could now apply myself

to getting—nay, demanding—answers. My questions became like little

people in my mind, running around shouting at other little people and occassionally

knocking one of them down. How exciting and how refreshing this all seemed!

With

this thought in mind, I began to turn up the mental heat. There in fact seemed

to be two big questions: First, were there hatchery fish to be found in the

creeks where I wanted to fish? Second, would I know the difference if I caught

one? These thoughts almost made my head hurt. But it was good, as I was no

longer thinking about the other thing. Al Queda, anthrax, bin you-know-who

(okay, I shouldn't even be saying those words) were now far from my mind.

I had bully questions, something reporters love, and I could now apply myself

to getting—nay, demanding—answers. My questions became like little

people in my mind, running around shouting at other little people and occassionally

knocking one of them down. How exciting and how refreshing this all seemed!

Having done a little more reading of the regs, I decided it was time to call Fish & Game and get some answers. The regs listed the office, located in Yountville, responsible for the coastal area north of San Francisco. I gave 'em a call, got a real person on the phone, told 'em what I wanted, then, after a minute or two of being on hold, was told that the person I needed to speak to would call me back. I was baffled; the "real person" sounded a little baffled too. It was my assumption that the person I needed to speak to, John Emig, was there when I called but suddenly became unavailable. I waited for the return call, which did not come, then called again the next day and left a message. No response. I called the main Fish & Game office in Sacramento, asking for press relations, something I prefer not to do, and got a real person, Steve Martarano, who gave me the name & number of a real person over in the Yountville office, Tracy Love. I called Love, who turned out to be real enough but not the right person. However, Love passed the message on and soon a call came back from Emig. Emig sounded distracted, as though there were other things on his mind. Hopefully some questions about fishing would make him focus. God only knows it is tough.

I asked Emig if my perception were correct that fishing was now very restricted on the coastal area. He confirmed that it was.

"It has been that way for two or three years," he said, explaining that it was the listing of the steelhead by the National Marine Fishery Service as threatened that had caused the restriction. Okay, I understood that he was not personally to blame for the situation.

As to the likelihood of finding hatchery trout or steelhead in most creeks north of the City, Emig admitted that there would not be, as I worded it, a "chance in hell." That is because hatchery fish are released in only two locations—on the Russian River at the Warm Springs and Coyote Valley fish facilities. This is to replace runs of steelhead impacted by dams of the same name. Says Emig, "Before the dams were built there were substantial areas above [the dams] where the fish spawned, and those hatcheries are there to replace that run of steelhead." The facilities in fact represent a deal worked out between water interests and fish interests. Should these dams be called damns? Perhaps.

Thus, while a stray might make it up to, say, the Greenwood Creek in Mendocino county, the chance of it happening was about a million in one. Thus the regs were really discussing the possibility of a miracle occurring, like the second coming of Christ. The regs might just as well have stated the keeper limit as zero. Or put another way, the policy is "catch and release."

If fact, the practice of releasing hatchery fish into a stream with native fish is questionable, as the hatchery fish are competing with the natives for what may be limited resources. Thus a miracle in this case is not necessarily a good thing.

So if the National Marine Fishery Service is to blame for listing the steelhead as threatened, who is to blame for this threat? Let's get serious for a moment and pass the buck as far as it will go. Creek deterioration is thought to be the likely cause for the decline in steelhead populations, and sedimentation of creek beds is a part of that. Eggs either do not get laid in creeks with siltation or fail to hatch when they do. These are facts, not opinions. Says Emig, "There are problems associated with logging, road construction ... if there has been a land slippage, that would cause discharge of sediment into the stream." This should probably come as no surprise but, nevertheless, studies have been done that prove it.

A spot check of one pool in the Greenwood creek and one pool in the Navarro River in Mendocino county revealed heavy sedimentation in the beds. In the Greenwood creek, no fish or fry were observed in the pool. The Greenwood creek has been extensively logged upstream in recent times, some of the logging in areas right down to the stream bed. The pool in the Navarro River (shown below in November) was downstream of Anderson Valley farm lands. This of course represents no exhaustive study.

Another factor in stream quality is canopy around stream beds. If trees are cut too close to stream beds, then water temperatures can rise too high for fish to hatch.

Fish & Game is not monitoring all of the stream, says Emig, but they do have a program in place now "to assess the presence or absence of Coho salmon in many of the coastal streams this year." The program comes in response to a petition for listing Coho salmon as endangered. At this point the Coho is only a "candidate" for such listing, and Fish & Game is trying to determine if they should be listed. This has caused Fish & Game to look places they have not looked before. If they are not looking in every stream, at least they are looking in some.

The fishing news is not all bad, however. For the local view, I talked with Kevin Smith in Mendocino county, an avid sports fisherman and former commercial salmon fisherman. Smith says he has seen improvement on the coastal steams, part of which he attributes to habitat work. He has fished the Garcia and Navarro rivers and the Greenwood and Alder creeks. Says Smith, "There are good numbers of fish there in all of these creeks. The Garcia is particularly healthy at the moment."

The Navarro, he says, is "very messed up. Now that doesn't means there are not a lot of fish. There could be a huge run of fish there this winter; I don't know. They go up the tributaries up in the mountains up there, up Indian Creek, Anderson Creek, and further up all the way into Yorkville." (Photo below shows upper tributary of Navarro with good flow of water in December.) Some of those creeks still do okay for spawning, but says Smith, "the Navarro River itself is badly sedimented." This he attributes to current farming in Anderson Valley and past logging practices. To picture the Navarro both "messed up" yet full of fish, just picture one our major cities. Got the picture?

He attributes the improvement to better awareness of stream habitat, and in the case of the Garcia River, to a lot of work that has been done to improve it. As to the effect of the catch-and-release policy that has been in effect for the last few years on the coast, he says it is too early to tell. But he says that has been very effective in inland areas that he has fished. Says Smith, "I can tell you, on the inland fisheries that I'm involved with, it makes all the world of difference. Not killing fish makes a huge huge difference."

He cites the Tuolome River as a good example. He has been fishing there for over forty years. Fishing on the Tuolome is "better than ever," he says; and he attributes this to the catch and release policy. "The special regs there just made a huge difference."

Concerning Coho Salmon, Smith says they are almost extinct.

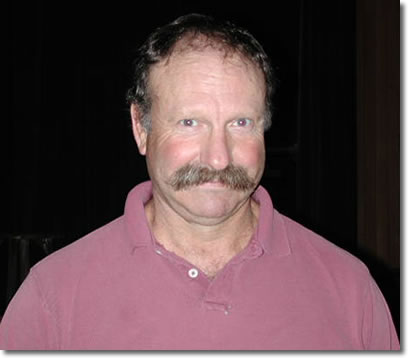

Special regs, fishing habitat, Warm Springs, Coyote Valley Fish Facility, hatchery steelhead ... I think you can see we have achieved a journalistic first here. We are talking and thinking about something other than all that bad stuff, about men in caves and men hunting men in caves, about dropping smart bombs and hitting your own guys, about wrapping one's body in explosives and going to meet the maker, who may in fact not be so happy with you after all, about ... well, the list goes on. But now I did begin to wonder. Thinking so much about creeks and streams and rivers, I began to wonder about that man-made channel of water, the California aqueduct. Just how safe was it from the "bad guys." Would they go after our drinking water? Would they poison us, make us sick? Make us puke till we were so pissed we wanted to make 'em puke big time? Certainly the president, who has gone from a president groping for words and concepts to a president who has found his niche and a language ("Bush") to go with it, wouldn't put it past 'em. But it left me wondering. And despite the thought that I would lose my journalistic first place for doing so, I called up the Office of Emergency Services to find out what the dangers were. I ended up talking with the Emergency Preparedness Manager and Chief of Security for the California Aqueduct—that's all one title—Sonny Fong. Fong is a guy much easier to get hold of than the Department of Fish & Game. Here there was no problem of focus, either. Fong was in the "here and now" but no spaced-out hippie.

The California aqueduct is 660 miles long, much of it an open target for madmen, or angry people who would do you harm. As a consequence, the security staff has been jacked up, though Fong is not giving out numbers. "I can just say that on all of our critical facilities we increased based on the need to cover specific strategic areas."

I asked if it were not a "mission impossible." There seemed to be about 660 miles of strategic areas. He admitted that the task was "very difficult."

The Department of Water Resources, which administers the State Water Project, which includes the aqueduct, is also working with other law enforcement agencies to watch over the system: the Department of Parks & Recreation, the Department of Fish & Game, who hopefully return phone calls when the chips are down, the California Highway Patrol, and local law enforcement agencies. Says Fong, "We are using other peace officers from other State organizations ... because they're in the area and there is overlap as far as what they are covering." Air surveillance is also part of the mix to nix mischief.

How dangerous is the threat? Says Fong, "With the open nature of the system, with the size of the system, we're very susceptible to biological or chemical agent introduced into the water. But knowing our system, and having proven our capabilities to respond to an incident based on our Y2K contingency planning and doing a lot of the exercises that we've done ... we know we can isolate given portions of that system. We know that it would take a substantial amount of biological or chemical agent, because we don't deal in gallons or millions of gallons of water—we deal in acre-foot."

No processing of the water is done while it is in the aqueduct. That is the job of the local water systems to which it is delivered. There are usually three phases of processing at the local treatment plants: coagulation and settling, filtration, and disinfection. Disinfection is commonly done with chlorine, but ozone treatment is also used as well as ultraviolet radiation and membrane filtration. Says Fong, "Both DHS [Department of Health Services] and CDC [Center for Disease Control] have run the tests and they've demonstrated that on most of the biological agents the normal processes will neutralize those biological agents." Fong says there is a dual system at work. First there is dilution of any agent dumped into the aqueduct, then there is treatment by the local water system. He says he knows of no agent that cannot be handled in this manner.

Testing of water is performed both by the State and water contractors, such as East Bay MUD or Santa Clara Valley Water District. Contractors for the water test for over a hundred different agents and will be testing for even more, says Fong, since they are now working with the military.... So far there have been no "incidents" on the state water project....

I cut the interview short at this point and thanked Fong for answering my questions. While it was an interesting discussion, and Fong seemed honest and straightforward, like so many of the people dealing with the current crisis, clearly I was losing ground; I was thinking about bad guys, bombs, botulism ... If I had been due some kind of journalistic award before, I know in my heart that the committee in charge of giving it would be having second thoughts at this point. I was as bad as the rest. I had not said bin you-know-who or al you-know-what, but it was clear where this was all leading. Disgusted with myself, I decided I needed to get away, and when that urge comes upon me I usually head up to Mendocino. That is what I decided to do. There you can relax, forget it all ...

You know Elk, that little town south of highway 128 as you come onto the coast from the Anderson Valley? The sign north of town shows a population of 250 but on any day of the week it looks more like 25. It has its little sin in the form of tourists these days but so does every other town on the coast. Fact is, there just aren't enough trees to cut down to earn a living. So instead of cutting trees, folks on the coast also bake little muffins and rent room to out-of-towners for their weekend trysts.

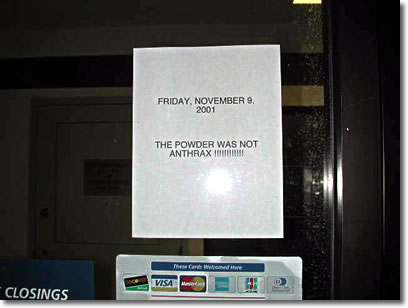

It was nice to be in Elk again. I spend way to much time in the City these days. And as I usually do, I stopped by the Elk Post Office to pick up my mail. (Okay, I had better confess; I have a little space out in the woods in Elk where I come to get away from it all and refresh myself. It is my "holy ground" but I would not kill you over it.) The new post office is located across the street from the old post office, which was once the offices of the logging company that started the town, L.E. White Company. The old post office is now a museum and has intriguing photos of early logging operations and piers built for loading boats over the high cliffs and of great catches of fish on the beach in Elk Cove. Oh, the resources of those times. This was back in ... Ah, you see how pleasant it is to let the mind wander back to simpler times. I pulled up to the post office and was about to enter—I think I as humming a tune—when I saw a notice on the door. I wanted to cover my eyes. It read: THE POWDER WAS NOT ANTHRAX.

Darn. Double darn. My mind had successfully evaded such thinking for over two hours, and here it was staring me in the face. Well, this was really not my fault, I decided. I had been good, I had stayed away from IT. The fact is, IT had come looking for me. It was not ABC News or NBC or MSNBC but it might just as well have been. IT was hunting me down and wasn't going to go away. IT was an obsession that resisted all therapy; it was a tune that was being pumped into every elevator shaft and played on every telephone line where a caller was on hold; IT was in your face wherever you went—the grocery store, the laundry, the rest room of your favorite bar and grill. You name it, it was there. It had become inescapable.

What could I do? I caved even worse than before. I went to see Charlie Acker, Elk's fire chief, who is also the manager of the local water district and writes a column for the local newspaper. In a small town people often wear several hats.

Charlie looked as embarrassed as I did when I showed up to pump him with questions about Elk's anthrax attack. But he was good natured about it.

Mail arrives at the post office in trays, he explained, and white powder was discovered in one of those trays. This started the Anthrax incident in Elk. Now let me remind you. We are not talking about New Jersey or New York City or even Los Angeles. Elk is located in rural Mendocino county 150 miles north of San Francisco. The last thing Elk residents expected was a terrorist attack there. Read about it, talk about it, see it on the news—yes, Elk has TV—but don't expect to be part of it. Elk, in fact, is where you go to be safe from the craziness of the world. "Common sense" actually exists there and even prevails much of the time. People may be crazy or mad—crazy in love or mad about the neighbors dog being lose and running the cattle—and people may be depressed and stay in all winter drinking wine or whiskey by the fire, but generally they are not trying to kill each other in devious ways. If you want to kill someone in Elk, you do it openly and for good cause. So an anthrax attack seemed a pretty remote possibility and not a whole lot of thought had been devoted to it by the Post Office, Emergency Services, which the fire department handles, or the Sheriff's Office. In short, protocol was not awfully clear when this incident occurred.

Says Charlie, "As it happened, the fire department had just received training the night before on what to do in this type of incident." But he says they were truly amazed to have an incident occur the next day.

"There was a different protocol between emergency services and the Post Office protocol. As I understood it, we were supposed to keep people from going in or going out." But he said that might have been interpreted as "leaving the scene.... The thing that I understood is that people were just supposed to stay put and you weren't supposed to have more people go in to get contaminated or people go out to spread contamination to other people." The fact is they had not had time to explore the possible scenarios that could occur and so there was some confusion. In a small town, things are usually simpler, and common sense, unlike in the city where those two words will get you a dirty look, can solve many a problem.

The Post Office, says Charlie, was inclined to go on with business as usual. "They said, 'just let people in ...'" But Emergency Services and the fire department did not go for that at all, says Charlie. Finally the county sheriff showed up, but according to Charlie, he had not been briefed on what to do. The fire department had the advantage, because of its recent briefing, so fire-department protocol was adhered to and all ended well.

The mysterious white powder was sent off for testing and it was determined after a few days that it was not anthrax. So what was it? Says Charlie, "They didn't test for what it was; they test for what it isn't...." I did not press Charlie. I did not care to hear some a priori inductive therefore-it-isn't logic applied out in the boonies; I come here to get away from the brain. But a clerk at the Elk Store filled me in: "Everybody knew what it was; it was cocaine." Ouch! So much for the concept of small-town innocence.

Charlie's other responsibility is Elk's water system, which consists of wells fed by the Greenwood watershed. About directives from the State, Charlie says, "We're supposed to be aware and there are probably some specific things, but to tell you the truth I haven't given it a lot of extra thought." The fact is, he says that it is possible for someone to contaminate the water system if that's what they want to do. In fact he says you could contaminated any water source. "I don't know how you'd keep 'em out." Bingo! We we're back to common sense again.

A few days later I was driving out in the central valley and near the junction of Interstate 5 and Highway 152. Highway 152 crosses the aqueduct just before the junction. It had been raining the day before, and for once it with very clear out in the valley. There was snow on the mountains, and the plowed earth in the fields was a rich brown color that I had not seen in the valley before. I parked my Ford 250 van on the west side of the aqueduct and walked over to the bank. While all the creeks, stream and rivers in the central valley appeared to be bone dry, this one was not. It was one big swift-flowing open artery of water.

There is a fence there to keep

people out and signs warn of the danger of drowning, but it is easy to get around the fence. In fact there were two fishermen on

the opposite bank. While I stood there shooting photos, one of them pulled

in a good size fish that sparkled silver in the sun. I don't know what

fishing regs apply there, but apparently he thought it was a keeper; it

went into his bucket. But clearly access was no problem. With 660 miles

of open water, it looks like it would take an army to keep people out.

The Department of Fish & Game and the Department of Parks and Recreation,

as backup anti-terrorist forces, were nowhere in sight. (I have a reporter

friend who calls 'em Fishy Games and Park & Wreck Creation, but then

they return his calls even slower than mine.) CHIPS for once was nowhere

to be seen.

it is easy to get around the fence. In fact there were two fishermen on

the opposite bank. While I stood there shooting photos, one of them pulled

in a good size fish that sparkled silver in the sun. I don't know what

fishing regs apply there, but apparently he thought it was a keeper; it

went into his bucket. But clearly access was no problem. With 660 miles

of open water, it looks like it would take an army to keep people out.

The Department of Fish & Game and the Department of Parks and Recreation,

as backup anti-terrorist forces, were nowhere in sight. (I have a reporter

friend who calls 'em Fishy Games and Park & Wreck Creation, but then

they return his calls even slower than mine.) CHIPS for once was nowhere

to be seen.

Now I think you can see that I have only partially succeeded in what I set out to do here. And certainly I deserve no prize for this. But I have at least demonstrated as "proof of concept" that it is possible for short periods of time to stay away from THE TOPIC. And that is a bit more than some publications can say. And maybe with more practice and determination I will be able to write a whole article on something other than IT. Laugh if you want, call me naive, but I do think it possible. True, I have always been an idealist, though not a fanatical one, as fanaticism can lead to awful things such as ... Well, you know what I mean. Be of good cheer! What's there to lose but an eye, an arm or a leg.

Home | City Notes | Restaurant Guide | Galleries | Site Map | Search | Contact