Home | City Notes | Restaurant Guide | Galleries | Site Map | Search | Contact

San Francisco, now and then. As the fog rolls in, now becomes then, gives birth to dreamy when. Oh, let us begin to begin to begin. Begin with some sin, as the end is still far away. Bakersfield. Fresno. Beijing. San Francisco. All wrapped in the mist that blows in through the bay.

"CONTIAMO LA MONETA"

(Let's count the money), said Enrico Banducci's grandfather to him one

day in Bakersfield. His grandfather had heard that Enrico, age 13, was

planning to go to San Francisco to study violin.

His grandfather had been keeping Enrico's money for him in his safe so that his parents did not take it. Enrico had earned the money playing the violin two or three times a week since he was six years old. His father, who took no interest in his musical abilities, made him practice in the garage.

Part of the reason he was going to San Francisco was to study violin with then-concertmaster Naum Blinder. Part of it was surely to get away from his parents, who beat him almost every day.

"I was not an unruly kid," says Enrico. "My mother did not like me from the day I was born." In fact, she had tried to abort him.

Enrico says that one day he was sitting under the umbrella tree where he could not be seen and was listening to his mother talking with his aunts on the back porch. The topic was abortion.

"Oh, yes," said his mother. "I tried to have an abortion but I couldn't."

"Who were you trying to

abort?" asked one of the aunts.

"Harry," said Enrico's mother."

Enrico

was born Harry Banducci, not Enrico Banducci. "Enrico" came

latter when he got involved in the night club business.

Enrico

was born Harry Banducci, not Enrico Banducci. "Enrico" came

latter when he got involved in the night club business.

She told the aunts she took "Philippine black pills," drank castor oil, and was jumping down off the bed to get rid of him.

When he heard this, Enrico said he started to cry.

His father was a bootlegger who had a mistress and paid almost no attention to his mother. Both father and mother were frustrated, angry people who took it out on their three boys.

One day his mother hit him over the head with a pan, knocking him unconscious for twenty minutes. This occurred, he says, because he accidentally dropped a laced doily on the floor. A neighbor who witnessed this particular incident wanted to call the police but Enrico talked the neighbor out of it, saying that it would only make things worse.

Now if the above sounds bad, picture this: One day his mother was beating him outside when the Greek vegetable man came by and witnessed it. He was so upset by what he saw that he told his mother that he would not sell her vegetables anymore. What was Harry's crime that day? On the way home from school he had loaned his coat to a black friend who was cold and he had arrived home coatless.

This was all back in Bakersfield in the 1920s and 1930s. Before the Hungry i. Before the Purple Onion. Before Enrico's Sidewalk Cafe ...

When Enrico and his grandfather counted the money, it turned out he had 10,800 dollars.

In a scene at the dinner table his father angrily opposed the move when it was announced, but by the age 13 Enrico was now a big kid—"I had a mustache already and I looked about 18 or 19"—and he simply told his father that he was going. He had in fact already purchased his train ticket.

Once in San Francisco, it only took a few days to meet people and get connected. It took about fourteen years until the Hungry i came about. Even in San Francisco one does not open a nightclub at age 13.

"BI(2)ZI" (nose), she said.

She pointed a finger at her lovely rounded nose. I was getting a lesson on the parts of the body. I was wondering how far she would take this exercise. Her blouse was low cut and revealing, her skirt short.

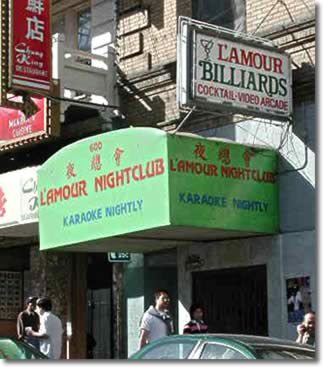

I was downstairs on Jackson Street in Chinatown at L'Amour. I knew the French word for love but not the Chinese yet.

A week before I was having a drink at Red's in Chinatown when North Beach old-timer Luciano started talking about the old Chinatown and some of the underground places. He mentioned one place up Jackson street where he said, "Even if I told you where it is, they wouldn't let you in."

Luciano was drinking Jack Daniels with a beer chaser and smoking unfiltered Pall Malls. His tastes, as you might guess, are on the earthy side. Then he mentioned a place down the street called L'Amour. Back in the old days, he said, there were girls in the back. "They didn't come out. You had to go back to them."

When my bartender friend Xiao Fan walked away towards the register, Luciano said, "You like her? She ain't got no ass on her?"

"Yes she does," I said.

"Maybe a little," he conceded. Luciano would be executed if the feminists ran the world. He once did jail time with Ken Kesey for drunk driving. Luciano is proud of that.

Well, I was curious about L'Amour.

Somehow I had never noticed it. I walked down the block, saw that it was where he said it was, big green awning and all, and decided

to pay it a visit at night when it was open....

saw that it was where he said it was, big green awning and all, and decided

to pay it a visit at night when it was open....

As soon as I sat down there was a young lady standing by me. I motioned her to have a seat. Would she like a drink, I asked. Indeed she would.

My drink was whiskey for $6, her's was a tiny glass of red wine—"hong(4) jiou(3)"—for $12. I knew from Enrico that playing the violin could be profitable if you were good at it, but drinking bad red wine? There was one prerequisite, however: you had to be female and pretty.

While her attire was much like that of a prostitute, a few questions revealed that she was not. She was from Beijing, had no family here, was a student, and had been working at L'Amour for three years, seven days a week, to pay her rent. The small glasses of wine meant more profit and staying sober to drink more $12 glasses of wine with customers.

What baffled me was this: the clientele seemed to be 100 percent Asian; and few were, as she informed me, willing to fork out $12 for a drink for her. So where did she make her money. I'm still trying to figure that one out. We did, however, discuss a future relationship in which I would help her with the rent.

She likes soft music and the saxophone, she tells me. "What kind of music do you like?" she asks.

"Jazz," I say.

"Too loud," she says.

"Not all of it," I say.

Her smile is immediate and refreshing, like cold water on a hot day. She has an inner glow that shines like a gem through her dark eyes. She says she misses her family in China. And why is she so far away from home? I didn't find out.

Her name is Shua-jing, which means crystal in Chinese. She goes by that name as an American nickname. I call her Shua-jing.

The setting: a big downstairs basement room with a bar at the back wall with chrome and red neon lighting. Some nooks and crannies off to the side, apparently no longer used for anything but storage, as my prying eyes soon discovered. And little "living rooms" settings around the big main floor, all enclosed by low partitions. I watched while one Asian gentleman, who needed to go to the restroom, simply lifted out the partition next to him to avoid stepping over his companions. The act seemed like an indelicate violation of a fragile structure in a structurally deficient environment, but it got him to the restroom quickly.

Once upon a time the place must have been lively. The stairs leading down to L'Amour are not those narrow kind that you find all around Chinatown. They are more the big stairs leading down to a ballroom. And the doors are wide double doors. The sign outside advertises pool. If there was once a pool table, it is long gone. While spying around, I noticed an area in the back that probably once housed the pool table. I can almost picture a young Asian man, cigarette dangling form the right side of his mouth, bent over a green-cloth table, eyes moist, tense, making quick preparatory thrusts of his cue through an apperature formed of thumb and forefinger, while sighting the imaginary path of balls; and I can almost hear the clack of one ball striking another then another then another untill three balls drop into corner pockets and the game is over and the young man walks off towards a back room, ready to relieve his tension.

Now the entertainment, if you want to call it that, is karaoke; it is music minus one, Asian style. You take the microphone and sing along to a dramatic video that is minus the vocal sound track. The words are displayed at the bottom of the screen in case you don't know them. The typical video features a highly anguished young woman almost always by the seashore, waves breaking in the background. "Sturm und drang" in German. The volume is very high so that it is difficult to make any aesthetic judgment about a participant's performance. To be fair, it looks like good fun in a tacky sort of way.

Given the small customer base, there seems to be much too much open space by Chinatown standards. Maybe that is why drinks are $12. They are paying for the vacant real estate.

"_____ yong(4) Zhong(1)wen(2) zen(3)me shuo(1)?" (How do you say _____ in Chinese?)

In the interest of efficient learning, which I really do not believe in anymore, I asked her how to say, "How do you say?" It is that one phrase, in any language, that opens up the language. It is the little tool that allows you to rob the language bank.

The music was loud and she had to say the phrase two or three times in my ear for me to hear it and get it right. Also, there seemed to be subtleties in the pronunciation that went beyond any rules that I learned so far. It was pleasant to be leaning something this way. I could feel her warm breath in my ear. No wonder I had spent so much time staring out the window learning English grammar way back when. The teacher did not hold your hand, press her leg against yours, and tell you you looked very romantic. So you stared out the window.

"Do you like Chinese culture?" she asked. Her English was limited and I think she had that question straight out of one her classes. I did not want to lie to her or give her a stupid answer. Chinese culture was a big topic. I knew only a small part of Chinese culture. Considering the antiquity of Chinese culture, it was a little like asking if I liked life on earth or existence in general or approved of the job god was doing as the universal CEO. My friend Xiao Fan had introduced me to some unusual food recently, but eating duck legs and tongue did not make me an expert on Chinese culture. Far from it; it had left me with an unusual taste in my mouth and a bit of skepticism.

She pointed to her lips, which were full and inviting. "Zui(3)ba(1)," she said. I tried to kiss her and she moved away giggling. I was being a bad student. That is not what she had in mind.

"How do you say 'pretty mouth?'" I asked.

These are the lessons I like these days. I go to school in underground bars....

THE MONKEY BUILDING. This is where Enrico first lived

when he moved to the City at age 13. It was on Montgomery street, not

the one you know today, which is a cool concrete canyon that gets but

a few hours of sunlight a day, but the Montgomery street of 1936. William

Saroyan also lived there, as did Benny Bufano, and later on Jack Kerouac.

Enrico used to meet with Saroyan

at the original Black Cat. Now there is a Black Cat (left) across the

street from Enrico's on Broadway; and if it were not across the street

from Enrico's it would probably get its fair share of business. It is

not a bad place at all. But the  original

Black Cat was located at the corner of Montgomery and Jackson, and it

was as exotic as a peacock.

original

Black Cat was located at the corner of Montgomery and Jackson, and it

was as exotic as a peacock.

"The Black Cat was the place of San Francisco," says Enrico. "You could get anything you wanted there. Oh, what a cafe that was! Somebody sitting at the piano and he was gay and someone was singing ... and it smelled great. There were all kinds of smells in there."

"He used to say, 'We're from small towns, Enrico.' I'd say, 'So what? We're doing alright; what the hell, you're doing great.'" Saroyan was. He was the man about town then. As Herb Caen said, he seemed to be everywhere all at once.

Saroyan would say, "Yeah, well, sometimes I wonder about myself. I think the Armenian thing blocks me many times." And Enrico would say, "Oh, cut it out." And Saroyan would say, "I wish I were from a family up on Pacific Heights."

"Oh, no you don't," Enrico would say. "You wouldn't have been you." Then Saroyan would admit that he was right. But he had the feeling that things might have gone easier for him had he not been Armenian.

Things would certainly have gone easier for Saroyan's father, about whom Saroyan once wrote a story. Saroyan's father was also a writer, though completely unknown, and apparently quite a good one. The story was called "Myself Upon the Earth." In the story his father makes the trip to town dressed in native costume and walking, not riding a bike as was the custom among the farmers in Fresno. An Armenian friend stops him along the way, telling him, "You cannot do this thing ... People will laugh at you." Then let them laugh, says his father. "These are my clothes."

Saroyan's father was dear to his heart, unlike Enrico's father to Enrico. "One day at lunch," says Enrico, "he said that he wanted to follow in his father's footsteps. His eyes would glow when he was talking about him."

In one of his books Sayoyan says his father used to write on wrapping paper which he turned into books. When Saroyan's father was alone in New York, working as a janitor to get enough money to bring his family to the United States, his journal said he only had two moods: "sad" and "very sad." If he'd done his time in San Francisco as a janitor he might have at least experienced a wider range of moods: "manic" and "depressed."

There is another wonderful story that Saroyan wrote about his grandfather, Melik. The story is "The Living and the Dead." In this story Saroyan's grandmother, who has come to the "new world" and lives in the same house with Saroyan, says that they do not make men like Melik anymore. "My husband Melik was a man who rode a black horse through the hills and forest all day and half the night, drinking and singing." He was hated—bitterly hated—by friends and enemies alike, she says.

It's a matter of being yourself, of being impervious to what anyone thinks of you. I don't know the Armenian expression for this but I'm sure it is very beautiful.

Home | City Notes | Restaurant Guide | Galleries | Site Map | Search | Contact