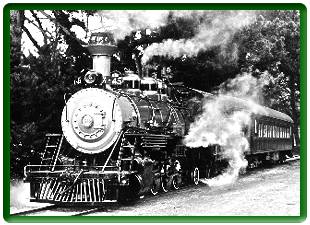

Old No. 45 on the Skunk Line

Old No. 45 on the Skunk Line

| Smelling a Skunk -- Lumber Politics in Mendocino |

| By Jennifer Poole |

|

Along the historic Skunk Train line in Mendocino County there's a slope so steep the railroad cars have to travel eight miles of loops and turns to get one mile forward. It's a beautiful place, lush and green, with little creeks and waterfalls everywhere during the rainy months, and wildflowers in the spring. Tourists and railroad buffs who come from all over the world to ride the old logging train always pull out their cameras at this spot. There are big trees here, too, more than anywhere else along the railroad's route -- old growth redwoods and Douglas firs that grow in a narrow strip along the curving tracks. About half of the old growth in this scenic corridor was logged 20 years ago, but there are still enough ancient trees growing closely enough together, 97 acres of them, that the California Department of Forestry considers this to be an actual old growth forest, the very last such forest in the entire Upper Noyo River watershed. In 1979, popular opposition to the extensive logging carried out by the Georgia-Pacific lumber company within sight of the Skunk Train inspired a voluntary agreement that limited logging along the tracks. Harvesting guidelines were accepted by G-P, the second largest timberland owner in Mendocino County, as well as other landowners adjoining the railroad right-of-way. However, G-P refused to sign on to a renewed agreement after it expired last year, and has since put its 195,000 acres up for sale. G-P officials say they expect the sale will be complete by the end of this year. In the meantime, company foresters have been filing timber harvest plans at a very rapid rate in the last few months. At the end of September, G-P submitted a 456-acre plan with borders drawn to include the old growth trees growing along each of the railroad loops on the switchback hill. Not all of the big trees are marked for harvesting, but logging is proposed in 72 of the 97 acres of old growth still standing, and several small areas of old growth right next to the tracks are marked for clearcutting. Overall, an average of 30 percent of the total timber inventory on these 456 acres would be logged, and the denser forest would be cut even more heavily -- between 50 and 85 percent in some sections. Cynthia Johnson, the great-granddaughter of Union Lumber Company founder Charles R. Johnson, who built the Skunk Train to haul logs to his Fort Bragg mill, and once owned all of what is now G-P land -- said she was "appalled" by this proposed logging. "My father told me he deliberately left the corridor along the railroad, as he had learned from his father," she said. "I wouldn't go so far as to say he wanted it ‘preserved' -- they didn't think in those terms in those days -- but he did want that area left alone, so it was pretty, and so the tourists could enjoy those big trees along the railroad." Johnson said G-P had recently filed a harvest plan for an area behind her own property, near another part of the Skunk Train line. "That was logged 20 years ago, too," she said. "That part of the forest hadn't been cut for 90 years when G-P came in and logged it in 1979. I grew up with ‘sustained yield' as a household word. We knew how important it was, for the longevity of your company and for the forests themselves. The fact that they're relogging areas where they cut just 20 years ago doesn't show much respect," she said, "not only for the forests but for the people who are working for their company." In fact, said Linda Perkins, a local timber activist who attends weekly California Department of Forestry timber harvest review meetings, G-P has been filing harvest plans for areas they logged as recently as 1995. "This is the last rakeover," Perkins said. "G-P is in the same pattern that Louisiana-Pacific was in before they left, reentering places they were logging only four or five years ago and going after the best of what's left." The Skunk Train board of directors is not objecting to plans to log one of the most beautiful and popular sites on its itinerary. G-P proposes to use the railroad to ship the logs to the Fort Bragg mill, which would be a big financial shot in the arm for the Skunk, which could use a little extra cash. Gary Milliman, Skunk Train president, couldn't comment on the particulars of the logging plan since he hadn't yet seen the 240-page document. "I really need to see the THP," he said, "and to go out and look at it, to be able to assess what the impact would be. But, you know, the Skunk Train was always a logging train. There've been logging activities along the right of way before, and that's part of the story we tell during the excursion." G-P's local resource manager, Tom Ray, made the same point. "Logging and hauling of logs on that rail line are historical uses for that area," he said. Although Ray confirmed that G-P foresters did not follow the scenic corridor guidelines in developing the plan, he said that "aesthetics were carefully considered." Local environmentalists and fans of the railroad were heartened, however, when CDF rejected the Skunk Train logging plan on first review. The plan was returned to G-P with a list of 33 problems that must be addressed before the plan can be accepted for filing. Some of the items are technical in nature and easily fixed; others indicate that CDF is paying closer attention than usual. The first issue to be addressed is the cumulative impact on old growth -- or the "late succession forest stands," to use the technical forestry term. "Most of what they wanted was simply more information," said Ray, adding that G-P planned to resubmit the plan at some point. But when this happens, fishermen's associations, railroad aficionados and statewide environmental groups are expected to formally object to the Skunk Train logging plan. Other agencies like the National Marine Fisheries Service are also expected to scrutinize this plan carefully. The Noyo River is still the freshwater home to a number of wild coho salmon, and has already been designated an "impaired waterbody" by the Environmental Protection Agency, due to sediment from logging, road building and other human activities. It's unlikely that federal agencies charged with preventing the extinction of the North Coast's salmon population will look kindly on such a large harvest plan in the headwaters of the Noyo River. During his election campaign, Gov. Gray Davis promised to save all of California's old growth trees "from the lumberman's ax." Although his spokesman now says that Davis was referring only to the Headwaters Forest, many of his constituents still expect their new governor and the CDF -- with its new director and several new Board of Forestry members appointed by Davis -- to make good on that promise. For more information on riding the Skunk Train, call 1-800-777-5865 or log on to http://www.skunktrain.com. |