Home | City Notes | Restaurant Guide | Galleries | Site Map | Search | Contact

Navarro Beach,

Mendocino County, California

Whose Coastal Getaway Now?

By Louis Martin

The Quick Stop in Cloverdale is crowded as usual but after taking the turnoff to Mendocino and the coast, traffic thins out. Except for a hippy in an old blue pickup who is following dangerously close—doesn't he know hippies are supposed to be mellow?—I am beginning to get away. I pull over and he passes.

Beyond getting away, there is a purpose to this trip, but in hot weather purpose can be forgotten. I remind myself that I have come to shoot photos on the coast.

However, Yorkville Cellars winery looks cool and inviting, and there is still time to get over to the coast. "Where are you from?" asks the woman behind the counter in the tasting room. She is wearing a burgundy T-shirt, is pale and has a nice country-frazzled look about her. The only other car outside has a bumper sticker on it that says San Francisco Blues Festival. Since there is no one else in the the tasting room, I assume it is her car.

"San Francisco," I say. "It's hot there too."

"Really?" she says. "Well, the temperature over there"—she points to a gauge that must be located on the outside corner of the building—"read in the nineties yesterday."

Inside the tasting room in

the shade of the big oak trees it is cool and comfortable. It is located

at the base of a hillside vineyard overlooking valley-floor vineyard and

Highway 128 through the valley. There is a big shady porch outside with

a view of the valley.

First she pours the blend, called Richard the Lion Heart, then a Merlot and a Petit Verdot that are used in it. The blend is the best, the Verdot a little thin. There is Cabernet Sauvignon and other varietals in the blend, all grown on the surrounding vineyard, but I don't have time to try them all if I'm going to get to the coast while there is still light. I explain why I need to get going.

"Well, the light should be good," she says, adding that there is going to be a full moon tonight. I am not planning to shoot in the moonlight but the information is welcome. In Mendocino a full moon means more than just a round, yellow orb in a night sky; it means possibilities, mysteries and enchantment, and it means other things that women seem to best understand.

Coming off the last winding curve in the hills, the road straightens out at the fire station as Boonville appears in the distance. It is the big town of the Anderson Valley with a lot of Hispanic workers. There is one pickup in front of the Boonville Market and one car. It is a big market for such a small town and right now it is almost empty, the before-dinner hit to come maybe in a half hour. At the entrance is a rack of newspapers, with the lead story in the Anderson Valley Advertiser on mineral wells. Inside the market there is much of what you would find in a Cala Market in San Francisco with the exception of a large row of straw hats. It is hard to imagine that many heads in Boonville in need of that many hats, but maybe they get blown off in the wind and crushed by cows or pickups.

The chubby checkout girl is all smiles, as though having been raised on natural good humor which she now freely dispenses. I remind myself that I have an appointment on the coast where temperatures should be cooler.

House of Berlincourt

Ted Berlincourt is a tall, thin man who likes to lecture using a collapsible telescoping metal pointer. He is a former Defense Department researcher. His wife, Marjorie, is small, a determined-looking woman, flawless in appearance. They may not be city people, but they are definitely not country people.

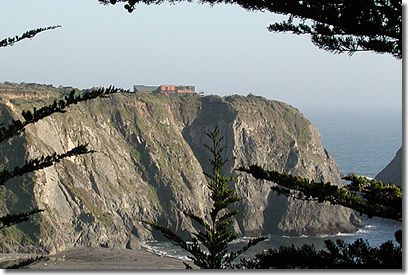

The Berlincourts bought a piece of property south of the town of Elk some years ago. They planned to build a retirement house there. The property is located on a bluff in an area designated "highly scenic" according to the local coastal plan of the county. Greenwood State Park, located on the Elk headlands, also looks to the south towards this bluff. The idea of this new house—all 31,000 square feet of it—squatting in plain view on the edge of the bluff was not popular with many townfolks.

Elk is no longer the lumber town it once was. And though some would hate to admit it, the town's economy depends heavily on its bed & breakfast inns. Truth to tell, it is more the magnificent view, less the morning muffin, that brings guests to the inns. State Parks, whose "guests" also come for the view, expressed concern for the loss of another "uninterrupted" view on the coast.

However, there appeared to be a sane solution: Move the house back from the bluff and over to the south, so it was not visible from town, park or B&B. This was what the county planning department asked when the building permit first came up for review. This solution, however, did not appeal to the Berlincourts, and they appealed to the county board of supervisors. The board, at the time liberal-leaning and favorable to the California Coastal Act, ruled against the Berlincourts too. (See Dream House Voted Down in Mendocino County.)

But the story did not end there. The Berlincourts waited for a new, more-conservative board of supervisors to be elected—something that does not take very long to happen in Mendocino—and they appealed again and won. Now enter the Sierra Club and a group called Coastwatch. They appealed the decision to the California Coastal Commission, which approved the project subject to "conditions." One condition required that the house be screened from view by vegetation.

According to Robert Merrill,

district manager for the North Coast office of the California Coastal

Commission, the condition requires planting of a drought-tolerant evergreen

screen of 200 or more trees and shrubs. As it is expected that many will

die, this condition also states that one-third must remain at maturity.

A tree maintenance program is required along with the filing of a yearly

report. Planting must begin within 60 days of the completion of the house.

Merrill concedes that it may prove impossible to screen the house. The Berlincourts claim that they have successfully planted trees on the property before. But says Merrill, "If it doesn't work, they are at least supposed to recommend corrective actions. If it just proves it's not feasible, then we might be suggesting that they seek an amendment that changes that requirement; maybe there is some other approach that could be used, like berming."

There is some question as to what is meant by "screening" the property from view. The conditions do not state that it must be completely invisible, according to Merrill. "I suppose it could be that you might see tiny glimpses of the building between the trees, and I think that would be consistent with the permit."

Hiding the two-story house behind vegetation may prove difficult, however, as it is located on a jutting, wind-swept bluff where scrawny native shrubs are hard-pressed for survival.

And what if the Berlincourts don't follow through with screening the house, which is nearing completion? While this seems unlikely, in general enforcement is a problem, says Sara Wan, chairperson of the California Coastal Commission. "You have people who get a permit and then don't bother to pay attention; once they get the permit they basically do what they want ..." (See sidebar on How the California Coastal Commission Operates.)

Postscript

Not far away to the north is Navarro Beach, once the scene of much haggling between State Parks and a homeless camp. Navarro Beach was once a wild place, and to a certain extent still is. Characters such as Diver Dave, Spider, and Mayor of the Beach Robert Jarrell lived there in old trailers, buses and tents. And an Indian lived out on the point in a tepee. Diver Dave came to Navarro Beach for healing after a motorcycle accident that left him partially disabled. He got his name from diving for abalone to feed those on the beach.

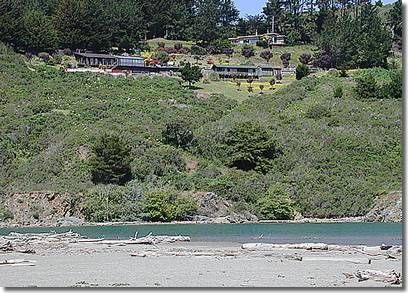

Navarro Beach is a big flat

sandy beach at the bottom of the Navarro River, which spreads out into

a broad lagoon before spilling into the ocean. It has high bluffs all

around it and once felt awesome and remote. Now it is a State Park and

still has an awesome quality about it, but when you look up over the Navarro

River now you see houses on the hillside.

Diver Dave used to enjoy making enormous bon fires on Navarro Beach. There were no State Parks fire pits on the beach then. He dragged together all the driftwood he could find, piled it high, Indian style, then lit it at night. You could see Diver Dave's fires for miles. They looked like the scene of an airplane crash or a city on fire where there was no city. People used to call in reports about an enormous conflagration on the beach. But the local firefighters knew it was only one of Dave's fires. "It'll be out in a day or two, ma'am. Nothing to worry about."

Now State Parks has nice little circular fire pits on the beach, and if you want to make a fire, you must make it in one of those pits or face a fine. As Diver Dave said about beach fires, post eviction of the homeless, "You can cook a hot dog there, but it is not a happy fire." (See Navarro Beach Retrospect.)

At night, though, with a full moon over the water, it is still spectacular. But it may not be the getaway you once knew.

Home | City Notes | Restaurant Guide | Galleries | Site Map | Search | Contact