Home | City Notes | Restaurant Guide | Galleries | Site Map | Search | Contact

There are thieves, preachers, poets, murderers, healers, lawyers, and fundamentalists everywhere you go. They just wear different costumes, pick up different props.

On my first day in Chattanooga,

Tennessee, I noticed that there were an awful lot of waffle houses. I

had recently relocated from Santa Cruz, California, leaving the bedrock

of nonconformity for the very buckle of the Bible Belt. I had decided

that I would delve headfirst into my new surroundings. I wanted to find

the real "deep South," whatever that meant.

Thus, I entered one of these

waffle houses, an especially prosaic looking one, or so I thought. Inside,

there were a few people who looked like they’d escaped from an episode

of Jerry Springer. A song came on the juke box. It was the Confederate

anthem.

People everywhere were still

talking about it. The Confederacy. Even the college newspaper still had

something to say. Folks back home had told me it was going to be like

this, but I had told them they were being too judgmental of our Southern

countrymen, indeed prejudiced, for surely these countrymen had already

"gotten over" a war that had ended more then a hundred years

ago. The truth is that people in the South have not recovered from the

Civil War, which they still refer to as "The War." They still

talk about it as if it happened yesterday, discussing certain key battles

over dinner.

Meanwhile, back at the waffle

house, I was experiencing the first reverberations of culture shock. Suddenly,

I didn’t know how to behave. There I was in this waffle house, which

looked like it was probably the first waffle house ever, and everyone

was looking at me as if they knew that I was from very far away.

I sat down at a two person booth. There was a newspaper on the table, and on the cover of the newspaper there was a story about a man getting arrested for inhaling Freon from air conditioning units on top of buildings. A large waitress with stringy blond hair asked me a question but I was unable to understand a single word she said. I asked for coffee and cream. I looked at the menu, but the menu baffled me. Where were the fruit salads and bagels of my homeland? Here people ate pork chops, grits, and fried liver for breakfast. I realized that I was now immersed in a culture that I’d only imagined, read about, and seen portrayed, but never actually experienced.

I started

asking people right away if they knew where any of those snake-handling

churches were. I’d heard about the churches from a segment on one

of those "Tales of the Bizarre" television programs. The program

explained how in the hills of Appalachia, people, many of them missing

teeth and wearing overalls, gathered in small churches and danced around

with rattle snakes. In addition to waving poisonous vipers around, these

people drank strychnine and burned themselves. They did these things because

of something it said in the Bible. And they did these things, many of

them, without getting hurt, though some of them did die. They were true

believers looking at the camera with defiance and pride.

Nothing gives rise to "characters"

like the thick, loamy soil of Appalachia. After a few short months, I’d

heard more than just a few stories. Southerners tell the best stories,

with a natural flair for adjective and metaphor, and they tell them with

very little provocation and as if they had all the time in the world to

reminisce about quirky high school geography teachers and the time it

snowed three whole inches. I never knew what it meant to have neighbors

before I moved to the South, where baked goods and invitations to back

yard barbecues are still de rigeur.

Everyone seemed eager to humor

Yankee inquiries about southern culture, pointing in the direction of

the best fried chicken establishments, laughing politely when I complained

about the humidity, pretending to be mortified that I’d never seen

fireflies before. But when I asked them about the serpent handlers, they

froze.

"I don’t think people

still do that," said my sixty-year-old, platinum-blond neighbor.

I did my homework and found

out that the country’s leading researcher and court appointed expert

on serpent-handling sects lives in Chattanooga, where he teaches at the

University of Tennessee. Dr. Ralph Hood is originally from California,

though with his long white beard and predilection for denim, he says he

always gets mistaken for a hillbilly.

"There is little or no

difference between a fundamentalist in Bali and one in Tennessee,"

he said one morning from a green leather arm chair that looked like a

toad stool that had sprouted up among the piles of books and papers in

his cluttered office.

"One just happens to take

up snakes?" I said.

"Serpents," he corrected. "They prefer the term serpents, because snakes are not poisonous. Serpents are."

Serpent

handlers are the wayward, mystical stepchildren of Pentecostalism

and the Holiness tradition, which hasn’t condoned serpent-handling

since states began outlawing the practice in the 1940s. When this happened,

the blue-blooded serpent handlers broke away from the Holiness Church

and continued to pick up rattlesnakes, mostly copperheads and canebrakes,

which grow to prodigious sizes in these hills. Serpent handling is illegal

in most Appalachian states, with Tennessee having some of the toughest

anti-snake-handling legislation. West Virginia is the only Appalachian

state where the practice is legal. There, it is illegal to catch serpents

unless it’s for religious practice.

The serpent handlers’

guiding text is Mark 16, versus 17 and 18, which states, "And these

signs shall follow them that believe; In my name they shall cast out devils;

they shall speak with new tongues. They shall take up serpents; and if

they drink any deadly thing it shall not hurt them; they shall lay hands

on the sick, and they shall recover." According to Mark’s Gospel,

these were Jesus’ last words on earth.

The snake handlers think of

themselves as "Sign Followers," and they are willing to risk

their lives to prove the extent of this belief. "Snake handling begs

the question, ‘How can you believe some, but not all, of what is

written in the gospel?’" says Hood, who has published numerous

studies on serpent-handling. His book on the psychology of fundamentalism

will be published this year.

The various churches operate

independently of one another but are closely knit, their congregations

meeting every season for revival-style "homecomings." Women

are expected to dress modestly in long skirts and blouses and to wear

no makeup or jewelry. Though worldliness in all its forms is disdained,

many serpent handlers drive nice cars.

Some of today’s Sign Followers

are fifth-generation serpent handlers. Powerful snake-handling families

often intermarry, a system Hood calls "spiritual Mafia." They

can tell you exactly how many times their great-great-grandfather was

bitten before succumbing. Serpent-handlers rarely enlist the help of doctors,

whom they disparage. No one under the age of 18 is normally allowed to

handle.

When someone does dies of snake

bite, it means that he or she must not have been "anointed"

by the spirit to do so. Handlers don’t believe that you should just

go around picking up poisonous snakes any old time. Only when the spirit

"moves on you" should you express and rejoice in your faith

in this way.

Since the practice started

about ninety years ago, at least seventy-one people have been killed by

poisonous snakes during religious services in the United States, including

George Hensley. Hensley is credited with popularizing the practice of

serpent handling sometime around 1910. While he may not have been the

first person in the twentieth century to handle a serpent in obedience

to Biblical text, he claimed that he was. He was bitten over four hundred

times before the fatal blow in 1955. Legend has it that Hensley, an illiterate

preacher and moon shiner in Cleveland, Tennessee (about 45 minutes North

of Chattanooga), first handled snakes while preaching on the Mark passage

one Sunday. At the end of the sermon, he took a large rattlesnake out

of a box with his bare hands. He handled it for several minutes, and then

ordered his congregation to handle it too or else be "doomed to eternal

hell."

Hensley’s fame spread

throughout Appalachia, catching the attention of the General Overseer

of the Church of God who ordained Hensley into the denomination. The practice

caught on quickly until Hensley was arrested for selling moonshine. He

escaped from the chain gang and fled to Ohio and from there to Kentucky,

where he started handling snakes again.

By the 1940s, the movement

had captured the attention of the media and local lawmakers, who began

outlawing the practice. However, Hensley and his followers continued to

handle, even when they were repeatedly arrested.

"It’s the rulers every time," Hensley preached. "It’s the rulers that persecute the people.... But I’ve handled ‘em all my life—been bit four hundred times ‘till I’m speckled all over like a guinea hen.... I’ll handle ‘em even if they put me on the road gang again! Now it’s handlin’ serpents that’s against the law, but after a while it’ll be against the law to talk in tongues, and then they’ll go after the Bible itself!"

Contrary to rumor,

handlers prefer highly venomous, freshly caught snakes because they’re

more lively and unpredictable. Serpent handlers often prefer to catch

their own snakes, usually the old fashioned way, which involves a snake

stick and a pillowcase. When a snake becomes sickly or old, they are quickly

retired. When handlers can’t find their own snakes, they purchase

them from professional exhibitors at prices they complain have been going

up in recent years. At last reckoning it was over fifty dollars a pop.

A Sign Follower has no use for snakes that look puny, and they are always

in search of new ones. After services, they trade specimens back and forth

in the parking lot.

Ralph Hood assured me that

there were plenty of Sign Followers, some within an hour’s drive

down nearby mountain roads. In fact, the religion seemed to be on the

rise; at last count there were over 2,500 members.

Hood likes to film serpent-handling

meetings. He has amassed a sizable library of such tapes, including old

super 8 footage of services in the fifties. Hood said the serpent handlers

liked and trusted him because he didn’t patronize them, or treat

them like precious oddities. For him, they were no stranger then anyone

else who decides to take something literally. In fact, he seemed to admire

their gumption.

"You’ve got to be

awed by that kind of faith," he said. "That kind of commitment

to faith. For them, there is only the supremacy of The Word. And The Word

is law. These people would sacrifice their lives for the word of god.

The thing that people don’t understand is that it is completely rational.

These people are far from crazy. They operate by a kind of logic."

So what’s logical about

picking up a copperhead and waving it around your head?

"What’s rational

about communion?" asks Dr. Ralph Hood. "Why doesn’t it

seem odd to us that people ingest the blood and body of Jesus Christ?

Because it’s familiar. Strangeness comes from distance."

Thanks to Tales of the Bizarre,

I assumed that serpent-handlers were inbred, toothless, fanatic hillbillies.

I was soon to learn that Sign Followers come from all walks of life and

are often well-educated members of the upper middle class. Except for

their thick accents, they might even pass for slightly aloof residents

of Humboldt County, California.

The media has never been kind

to the serpent handlers. TV crews routinely hunt out the most toothless,

crooked-eyed participant to interview. But in reality the pews are filled

with average-enough looking folk, many of them rural farmers, but not

all. While most Sign Handlers hail from the southeastern United States,

you will meet the occasional émigré from Detroit or Las

Vegas. Today there are groups of Sign Followers in many non-Appalachian

places as well, including Arizona, Michigan, and San Diego.

Sign Follower churches aren’t

listed along side the other denominations in the yellow pages. They meet

in small, nondescript, out-of-the-way churches, the kind with white paint

peeling off of them and with unpaved parking lots. When they can’t

find a church, they meet in brush arbors (yes, in the south, there are

such things), backyards, basements of old motels, or garages. Places with

addresses that do not show up on MapQuest.

So to get there you must have very good directions and even then you’ll probably get lost and have to ask somebody where the "snake church" is and inevitably they will give you a look and say something like "I think I heard of one of them places over up around that there old cemetery," and off you’ll go, down a windy road, past rusting Chevies and flatbeds, abandoned refrigerators, mint green shacks, and tractors. If you roll down the car window, you might be able to hear distant shouts, Hosannas and Amens, the soft sounds of a preacher whipping his congregation into a fury.

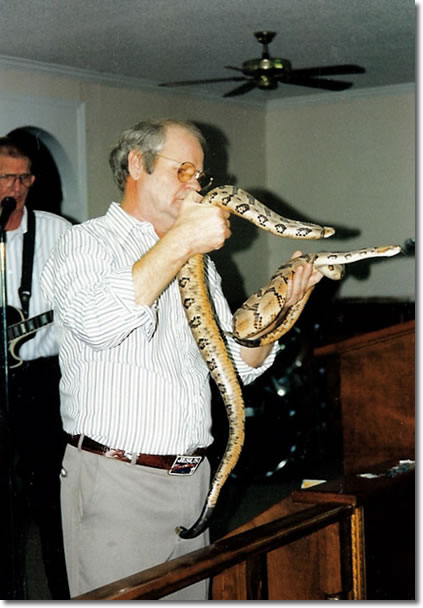

Inside the church,

fluorescent lighting and cheap paneling surround the closely knit congregation,

some of whom drive four hours to attend service, sometimes twice a week.

The air is warm and thick and filled with strange electricity. Tattered

Bibles held together with duct tape rest on the polished pews. The Reverend

Carl Porter, a dark yellow vest barely buttoned over his round belly,

approaches the stand and preaches about Jesus and related topics for almost

thirty minutes before I even notice what is up there on the stand next

to him.

"Jesus is real,"

he says. "Jesus made it all so he can handle it all."

His voice is rising and falling,

his rhythmic intonations gathering momentum, and then he looks over at

the plain wooden box on the altar. It’s about the size of a cigar

box. The kind of box you could use to keep snakes in. Or serpents.

Porter

bows down slightly and raises his hands above the box, praying over it

for a moment. Then he opens it and reaches in. What he pulls out of that

box hits the hot air like a revelation, darting it’s head crazily

as it sniffs. The reverend raises the fat copperhead over his head and

the thing seems to stiffen and freeze in the sudden brightness. It could

just be my imagination, but there is a new acrid smell in the air.

Porter

bows down slightly and raises his hands above the box, praying over it

for a moment. Then he opens it and reaches in. What he pulls out of that

box hits the hot air like a revelation, darting it’s head crazily

as it sniffs. The reverend raises the fat copperhead over his head and

the thing seems to stiffen and freeze in the sudden brightness. It could

just be my imagination, but there is a new acrid smell in the air.

"I have been anointed

by the holy ghost," he says and the people encourage him with hushed

amens. The band has started up again with another hymn that is reminiscent

of an early Elvis song. An old woman who looks like she stepped out of

an old daguerreotype, shakes a tambourine. It sounds like a rattlesnake.

"You’ve got to

have it, got to have the holy ghost," they sing. People are stomping

their feet, hands in the air. The Reverend himself starts to dance, hopping

a little on one foot and then the other foot, the whole time moving the

snake in front of his face and over his head. Sometimes he lowers the

snake towards his knee or waist, and looks at it as if not really seeing

it. Sometimes it looks like he’s singing to the snake.

Toto, I’m not in Santa

Cruz anymore, I think. I’m in the deep, dark heart of the South.

I imagine what some of the people I’d known in Santa Cruz might say

about the scene that is now unfolding before me. The snake as metaphor

... a spiritual struggle with faith made manifest ... possessing the sacred....

In fact, for a minute it is almost possible to imagine some of the fire

dancers and kundalini yoga practitioners I’d known out west handling

a serpent or two of their own.

People are shouting and clapping. Children are gazing wide eyes at the serpent, hypnotized. The snake is passed around the small circle of men near the pulpit while a white-haired woman starts singing a new song about finding her way out of the wilderness. People are in the aisles, quivering with the spirit, on the verge.

Home | City Notes | Restaurant Guide | Galleries | Site Map | Search | Contact