Surfer-Artist Defies Moon-Doggie Stereotype

Story and Photos by Nina Wu

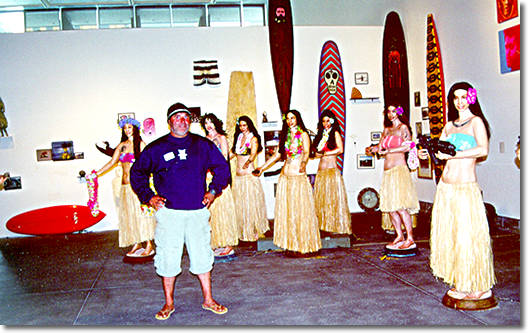

For California native Kevin Ancell (page bottom), there is no clear division between where art begins and surfing ends, or where surfing begins and art ends. The two are one and the same.

"I never met a surfer who wasn't an artist," he said. "Every surfer you meet draws the waves."

At least, every surfer that Ancell knows in his route while surfing both the northern and southern coasts of the Golden State. Ancell's works are currently on display at Surf Trip, the first Bay Area exhibit to chart the course of coastal California's surfing origins and culture.

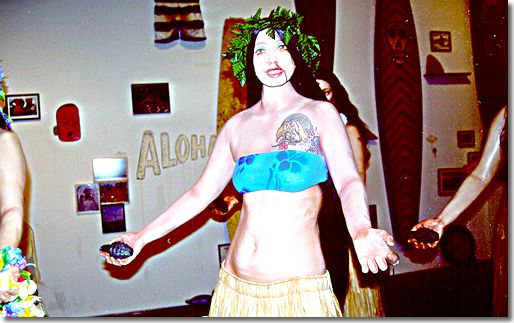

One of his works, "Aloha Oe," greets visitors as they walk into the exhibit. Aloha Oe is 25 life-sized hula dolls. At first glance, the hula dolls are dancing — doing circular amis, or hip circles — opening their arms in welcome while holding leis and ukuleles. But a closer look reveals that the hula dolls have bruised eyes and lips, needle tracks on their arms and tears of anguish coming from their eyes. Some of them are also armed with hand grenades and guns.

What's to be made of this? Aloha Oe means "farewell to thee," said Ancell. It's a commentary on the harsh reality of life experienced by native Hawaiians - a far cry from the tourist-driven perception of life on the islands as a tropical paradise. It's also a commentary of the effects of western civilization on Hawaii — it brought drugs, guns, and disease and pushed native residents from their lands. Downtown Honolulu is now full of as many strip joints and drug junkies as there are palm trees and mai tais. As Ancell put it, the classic story of "white man goes to a nice place and screws it up." The women were modeled after the dashboard hula that westerners turned into an icon of the "hula girl."

"Western civilization's kind of rolled over them," said Ancell. But these hula girls are fed up, empowered and no longer willing to put up with it.

"Now she's six-feet tall, she's holding a gun, and she's pissed," said Ancell, who lived in Kauai for several years and supports the Hawaiian sovereignty movement. "The small piece of sand and coral that she's standing on is all she's got left of her own identity and she's hanging on to it."

Aloha Oe defies the paradise image of the Pacific Islands. Likewise, the artwork in Surf Trip debunks the notion that all surfers are stereotypical blonde, shallow beach-boys who have nothing to say besides "what's up?" and "surf's up." In reality, the surfing community is global and multicultural, with a rich and art-inspiring history.

As mentioned in the exhibit, surfing originated in Polynesia more than 2,500 years ago, when the first Maoli king paddled his 17-foot-long, hand-crafted wood boat — called an Olo Papa He He Nalu — into the ocean and rode a wave. In the early 1900s, Hawaiian surf culture arrived on the shores of California and became a popular hit, particularly with television shows like Gidget.

The rite of passage for any surfer is to ride the waves in Hawaii, according to Surf Trip curator Bob Carrillo. Although surfers can now head to plenty of other destinations in Bali or South Africa, those who seek the roots of surfing must look towards Polynesia.

Over the past five decades, surfing evolved as an art form — and this is reflected in the surfboards themselves. The first surfboards were carved from redwood or pine with no fancy logos and colors, and measured up to 16-feet long. They became shorter — six or seven feet — over the ensuing years and were made of lighter balsam covered with fiberglass and resin. Since then they have been mass-produced using polyurethane. In the last 20 years, according to Carrillo, surfers have gone back to the roots of surfing by returning to longboards of about nine feet.

Carrillo traveled up and down the coast of California for the past two years gathering the art for Surf Trip. His goal is to "raise the level" of how people perceive surfing by eradicating the moon-doggie stereotype and presenting it as "a practice, way of life and rich source for artistic inspiration." He said the artistic community born out of surfing culture wasn't being represented. "You had many great contemporary artists that weren't being exhibited. So I wanted to create a place for that."

Ancell is one of the artists that Carrillo chose for the originality of his works. Although the works on display at Surf Trip are surfing-related, the themes of his works cover a broad variety of subjects and are often explorations of his inner psyche. His works have been exhibited at the Laguna Art Museum, the Santa Barbara Contemporary Arts Forum and Catherine Clark Gallery in San Francisco.

According to Ancell, surfing isn't just his life. It saved his life.

At the age of 10 his father committed suicide and he was adopted and raised by a group of southern California surfers. They were the movers and shakers of the 1970s surf scene, and for Ancell, surfing became a way of life as well as a teacher of discipline; it helped him meet challenges and overcome fear.

"Once you've gotten to a level that's really good, then you can do anything," Ancell said. "There's nothing that's out of your grasp once you put your mind to it. It builds your inner strength."

That is where the art comes in. For Ancell, art is an exploration of the inner self and another form of self-expression. The paintings on display at Surf Trip are somewhat foreboding; they are political commentary on the dark side of life. But they are also spiritual and replete with symbols.

One, titled "Burning of P.O.P." (1998), depicts the day Pacific Ocean Park burned down. That is where Ancell grew up surfing, and the painting is about the end of his youth. "The Death of Imagination" features an old and withering mermaid, who represents imagination. Ancell, like a lot of others, deplores the proliferation of the "dot-com" culture. He also has a personal axe to grind, as his art studio was recently purchased by a dot-com company. Ancell is in the painting at four different stages of his life, at one point carrying a small statue of Poseidon, trying to revive the mermaid.

Ancell explained his feelings about the dot-coms this way: "People's natural abilities to dream stuff up on their own is waning because of mass communications and mass technology," he said. "Everywhere you go, it's just sucked everybody in and their natural abilities are withering away. They're relying on technology now."

Another painting, titled "The Consumption of Fear," shows a skeleton draped over a surfer on his board in the ocean. "It's about the moment when fear totally consumes you," said Ancell. "Sometimes you'll be paddling for a wave and something will happen, like it'll shift on the reef funny and fear just swells out of the water and consumes you and it tears your spine out. Rather than go, you freak outů. If you go, you might make it. If you don't go, for sure you're going to get nailed."

"So there's the fat lady singing," he said. Brunhilde, from Wagner's Flight of Valkyries, sings from the bottom, left-hand corner of the painting, about a man's death with no glory.

"Anybody who says they're not scared, they're lying," said Ancell. "But you control your fear. As long as you respect the ocean, it'll respect you."

Ancell draws most of his inspiration from Manuel Ribeira — a Spanish painter who lived in Italy. He also draws inspiration from the works of Rembrandt, Caravaggio and the old, Flemish masters.

Though he now lives and works as a full-time artist in San Francisco, Ancell's past wanderings have included Mexico, Costa Rica, and China. In China he studied Wu Shu and taught American culture at the Beijing Institute of Science and Technology — until he was expelled for "improper political and spiritual activity."

When he's not painting, he's out surfing — or making surfboards. Two of his custom-crafted boards are also on display at the exhibit.

The life of an artist is rarely easy. Usually it's a constant struggle to keep the imagination flowing and to find curators interested in exhibiting your works. But surfing keeps Ancell going, along with a sense of humor. The recording on his telephone answering machine features a Hawaiian comedian: "Repeat after me: Life is bitchin'."

He compares surfing to dreams of flying: "If you're ever sad, all you've got to do is surf and it brings you right back up."